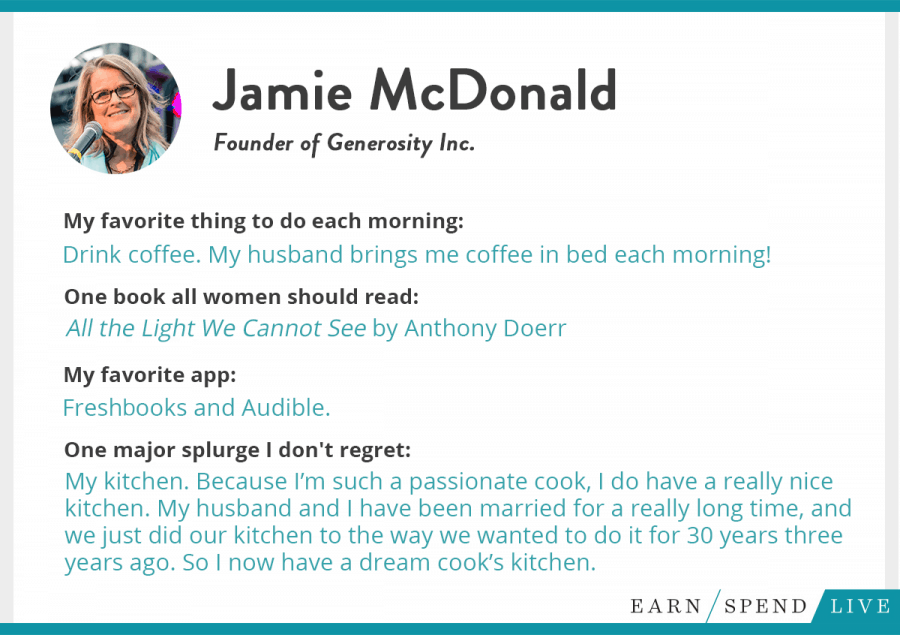

Real Talk With Jamie McDonald, Founder of Generosity Inc.

Jamie McDonald has had a varied professional career — from investment banking to being a three-time entrepreneur. We chatted with her about what it means to be a woman working in today’s world, how millennials have changed fundraising, and how she makes work-life balance happen.

Name: Jamie McDonald

Location: Baltimore, Maryland

Title: Founder

Company: Generosity Inc.

What it is: A firm focused on helping large-scale social movements and communities bring their communities together to scale the impact of their missions.

Educational Background: International development, Cornell University

Tell me about Generosity Inc.

It’s a firm that’s focused on helping large-scale social movements and communities and colleges and universities bring their communities together and really scale the impact of their missions. And so when I talk about Generosity, I don’t really think about it in terms of money, I think about it in terms of time, talents, and money.

What inspired you to start Generosity Inc.?

Well I sort of had two careers before this. I was an investment banker for the first 17 years of my career and then I became an entrepreneur. And my second startup was a software company that was focused on online giving and community building.

So that was really what led me to the work that I’m doing now because I really love the strategy and creative thinking that happens at the intersection of technology and activism. I was fortunate enough to sell my company in 2014 to GiveCorps Network for Good, who’s the largest online charitable giving platform in the country. They kept the software under their umbrella and I decided that what I really wanted to do was do this work without being tied to any particular technology.

There are a lot of great platforms out there, and different movements have different needs. I’ve enjoyed being able to work with a wide range of social movements and communities to help them tailor what their approach is in a way that works best for them. I’m very proud of GiveCorps Network.

So what does a typical day look like for you?

I view myself as a partner with people who are building movements around the country. Those movements range from things like givingTuesday to the way that colleges and universities engage young people in their mission, to movements that are focused on particular cause areas like environmentalism or poverty.

I can be thinking about five different things in a day that are all about how to the make the world a fairer more equitable place. So every day is different. I work with people all around the country, so I definitely spend a lot of my time on Skype and in various locations, travelling. But we’re so fortunate because we can do a lot of what we do without having to actually physically be side by side with people; we can be side by side virtually.

It’s really made it so that the value of experience and knowledge is much more transmittable. You don’t have to be in the same city to have an impact. And I really love that.The other key thing I spend my time doing: I’m also very engaged in my hometown of Baltimore. That’s the other part of things that this life has allowed me to do is to be very hands-on as a very actively involved citizen in my own hometown.

What’s been the hardest part about starting your own business?

While I’ve done it three times, and it gets easier each time. I think the first time out, you don’t have any idea what you’re doing. I don’t care how much you’ve read, I was in business for a long time before I started my own business and it’s entirely different. I think it’s hard to admit when you’re wrong, in the sense that you have a vision for what your business is—almost every person I know who’s ever started a business realized in a relatively short amount of time that they were about 50% right and 50% wrong with how they thought things were going to go.

You’ve got to be open to recognizing that quickly and being okay with the mistakes and viewing them as shifts in trajectory. So when you’ve done it a couple times before, it’s a lot easier to recognize that stuff quickly and shift and continue moving toward your best opportunities.

What’s been the most rewarding part about starting your own businesses?

They’ve each been rewarding in different ways. Honestly, my first business, I owned it for five years and I hated it from about the first month. I was done, but that is such an important learning experience. It’s really important to know what you want to do, what you don’t want to do, and what you are and are not good at. That first business really put me in a position where I was holding up a mirror to both my skills and my deficits.

In my second and third businesses, I guess what I’ve enjoyed the most is that I’ve really been able to take what I’ve learned in that first one and accelerate my ability to make an impact more quickly—and to recognize when I’m headed in the wrong direction much more quickly, and try to get myself on a more positive course.

You’ve mentioned your second and third businesses—what was your first business?

I know this is going to seem like a real departure—my first business after after I left investment banking was a very specialized gym.

We just worked with athletes, that was our focus. I’ve always played sports, always been into sports, I still play a lot of tennis and racquet sports. I’ve had kids who are athletes. It was just a really big part of my life, and I really didn’t go into it thinking that…I thought of it more as an investment and a learning experience. But the reality is, there’s just nothing like you being there.

And so as much as I was thinking I would just hire a manager, and we would go off and make a lot of money, it’s just not the way the world works. You’ve got to be part of it, you’ve got to be overseeing it every day and you have to really build it from the ground up. That was the most rapid learning experience of my life. I sold the business after five years, and I was very fortunate because I sold it a couple months ahead of the crash of 2008.

I had always assumed it was kind of a five-year thing, and my five years came at a good time. I was fortunate that I had an opportunity to find a solid buyer, and get out reasonably well. It was 2011 when we got [the second business] going. So I spent those three years focused on what I really wanted to do and Generosity Inc. is the place that I realized I wanted to focus my energy.

So your original career was in investment banking; what do you think you’ve carried into entrepreneurship from your previous career?

Well I worked for an investment bank that, when I started, was 2,500 people and when I left 17 years later, it was part of Deutsche bank, which is one of the largest banks in the world. I was very fortunate because it was a place that really valued entrepreneurs within their midst, so they valued people who could think creatively and make things happen, and I had the opportunity to start a couple of groups there.

So in a way I was being an entrepreneur there, but I was doing it in a safer context. It was not my money at risk, it was not necessarily my reputation at risk so to speak, it was the firm’s. But at the same time, I really had a chance to learn; that gave me the courage to launch my entrepreneurial businesses. So while it sounds like each of these tasks is different, they’ve all felt pretty natural as a sequence to sort of lead me to where I am today.

You’ve been in the professional world far longer than we have—so we want to know, how have you seen the professional landscape change for women?

I started my professional career in 1986, when I joined Alex Brown. That was the name of the investment bank at the time. There’s a whole lot that has changed, especially if you go back and look at pictures of professional women in the ‘80s—shoulder pads and perky bows that are like ties, they’re like big bows at your neck.

So crazy style, that’s certainly one thing. But I also think that today, women don’t have to pretend to be men to have the success of men.

When I had my first child in 1991, I was home from the hospital and back on the phone like two days later with work. I didn’t really take a maternity leave the first time, and you never would talk about family, you didn’t talk about home stuff much. It just was very different than today.

Today, I think there’s much greater understanding, for men and women, that we have much more 360-degree lives. And that is a plus, but it also kind of comes at a cost because, on the flip side, in a way we’re all expected to be available all the time, right? We’re so connected that it gives us more freedom, it lets us be more individual, but it also means that you’re expected to return emails at night, you’re just expected to act differently.

Then I think there’s just the more tactical things—it was, for the average woman, harder to make fast progress, it was harder to be seen as a peer in many instances. I can’t tell you how many times, even when I was the managing director, I would go to a meeting with a young, just-out-of-college male employee, and if we walked into a meeting, people would assume that he was senior to me.

And I don’t necessarily hold that against people; I think there’s a lot of conditioning that goes into that sort of expectation setting, but it was much more prevalent then than it is now.

Do you have any advice for working women in general?

I don’t know that I necessarily have any advice for working women that’s different from the advice that I have for working men. I think that part of what we need to do is to all be thinking about how to do a few things all at the same time. I think we have to recognize the high value of our talents and what we can bring to the table, while at the same time also recognizing what the other person across the table also brings and that it may not be the same thing, but it might be the more appropriate thing at the moment. That’s sort of a two-way street, right? And that’s just a working person’s thing is to recognize that you’re typically going to go further if you can put everybody’s talents to best use.

The other thing that I’ve become increasing more aware of in this just over-saturated information age is just the value of being a little more watchful. Synthesize what you hear before you talk. And again, I’m not sure that’s a man or woman thing as much as it’s just a success thing for me. I find that that’s a general issue that…and maybe there is a little bit of a woman’s thing in there in the sense that some young women I see feel the need to show they’re smart and wanna dive right in there, and I think that sometimes you can show you’re smart, but you can also answer the wrong question if you haven’t sat back and taken it and figured out what’s the real thing that’s being asked here and how can I best contribute to the discussion?

And again, I don’t think that’s so much a male/female thing, I think it’s an all-professionals thing. But I do think sometimes there’s a little bit more pressure on women to prove they’re smart, capable, and sometimes the best way to do that is to be the one who’s comfortable with the listening. Then weigh in with the best answer, not necessarily the loudest or the fastest answer.

You’re going to feel more confident in your answer if you listen to everything else, and then you proceed forward either with what you thought from the beginning or whatever your more informed perspective is on it once you’ve heard what everybody has to say. So it’s a fine line because I know a lot of people who say that women defer and they wait for men to talk, and again I think it’s not a male/female thing but that it’s a professional thing.

I once heard someone say that the person who controls the conversation isn’t the person who’s talking, it’s the person who’s asking the questions, and that has always stuck with me. So if you think about your professional life in that way, be the question-asker and then give your opinion or your recommendation, or your perspective, you will be giving a much better opinion or perspective because you’ve been asking the kinds of questions that will inform what you want to say.

Going back to Generosity Inc. Has social media has changed fundraising?

Oh yeah, totally. Because you can inspire people at scale. And that isn’t something you could do in the old days, right? A non-profit back before social media had to figure out ways to break through, and unless they had the money to spend on like really broadscale direct mail, or really broadscale traditional advertising, which most nonprofits don’t…it was really really hard for them to inspire people at scale.

And I think the other big thing that’s happened is that we’re not just supporting people around the corner anymore. It’s not just my church, my school, my synagogue, the Salvation army on the corner kind of thing, you can literally make a difference in the lives of people all around the world, and you can learn about that opportunity because of social media.

How would you say millennials have changed fundraising? If they have?

Yeah, I think they have. I think every generation has changed things a bit. I think that part of what we’re really seeing happening—and it was happening before the millennial generation—is this idea that they don’t view their money as their most valuable asset. They view time, talent, and money all as assets. And they really view those as more equal assets.

There’s a really good research and marketing firm called Achieve, that’s led by a guy named Derrick Feldmann and he every year puts out the Millennial Impact Report. He has a lot of data around that perspective of equal impact with time, talent, and money. So, I think that’s one aspect of it.

I think that the other way that millennials are really changing things is that because they have so much access to information and without even knowing it, they’re natural researchers, the expectation is that you’re communicating with them in a 2016 kind of way. What I mean by that is: What you and I both know—you’re much younger than I am—but you go to those websites, even if it’s to shop. And if you’re looking to buy something online and you go to a website that looks like 10-year-old technology, then you worry if it’s someone you really should buy from. It seems sketchy, right?

Even though it could be a perfectly legitimate, highly reputable company that’s been around for a long time, when their website is sort of clunky and doesn’t communicate to you the way you’re used to being communicated to, you question it, right? So, it’s why a site like Etsy works so well, because they’ve created an interface that allows people to see craft people in a more sophisticated way. Right? And so, the same is true with non-profits, and really the millennials and the Gen-X’ers have driven that.

We all expect now to see beautiful images, a compelling story, don’t overload me with data, let me go find the data. Tell me the story and then let me drill down the data. They want that human story first, and then they want to know that there are a thousand humans like the one you just told the story about. They don’t want it the other way around, like don’t hit me with the thousand number up front.

There are just so many things that they’re expecting to be different now in the way that they’re communicated to. And all of that is part of the fact that they’re digital natives. As I said, they’re natural researchers. And because they have access to so much information, you’ve got to break through with them in a way that is much more inspiring and compelling much more quickly.

If you could give yourself one piece of advice from when you started Generosity Inc., what would that be? Would you do anything differently?

I wouldn’t say that I have advice as much I have a hope that we’ll all understand that we can make a difference, that the world that’s out there and if we don’t think it’s working the way it should, with today’s access to information and technology, you can make a difference while sitting on your couch. You can give, you can be an ambassador for a cause by sharing information about it.

If you don’t have money to give, you can inspire others to raise money alongside you with crowdfunding. You can get hands-on involved if that’s what you want to do, but literally, people can create the world they want to live in without leaving their houses, and that is just not something that we could do even 10 years ago. So, that’s the thing I’m living today, is I’m trying to work on causes and movements that are creating the world that I want my future grandchildren to live in someday. And I can do that many ways without having to leave my home or my office.

Going more meta now, how would you define success? What does success mean to you?

You know, it’s a really interesting question, because I think you think of success very differently when you’re 50 like I am, versus when you’re 25 or even 30 or 40. Each decade, “success” feels a little different. For me, in my fifties, success really has three elements to it.

One, it has an element of impact. I am now an impact-maker. I am not watching others make an impact, I am leading the impact.

Two, it has a measure of control for me, so I want to work with the kind of people I want to work with on the kind of projects I want to work with, in the way I want to work with them. Meaning, I used to travel three days a week when I was an investment banker and that takes a real toll on you. So now I want to control not just what I work on and who I work with, but the nature of the way I work. That for me is definitely a measure of success.

And I think the third piece of it is a certain amount of serenity that comes with recognizing that you’re going to be largely right about stuff, you’ve got all this experience, and when you’re wrong, you’re wrong. You don’t sweat it, you don’t have those middle-of-the-night—I’m sure you have these too, I did when I was younger—I’d wake up at 3 a.m. thinking about the things I wish I’d done differently. And I constantly self-review to give myself feedback about things that I wish I had done differently, but I don’t sweat them the same way.

I just recognize it all as a continuum. You’re going to be right a lot of the time, you’re going to make good decisions, you’re going to give good advice, and be a positive partner in the work you do, but occasionally, you’re going to be wrong, you’re going to make mistakes, and that’s what happens, and you just can’t beat yourself up about it.

How do you balance your work and your personal life?

Yeah, I don’t really see it anymore as balancing. In some ways, my life is inherently balanced because I’m doing the kind of work I want to do and my kids are part of the stuff I do, in the sense that they…I’ve got a 25-year-old, 23-year-old, and an almost 18-year-old, so my adult kids, I mean, they’re some of my sounding boards. They’re millennials. I get their advice on things I’m doing and they’re part of my thinking.

I’ve been married a really long time now, almost 29 years, and so my family is part and parcel to what I’m doing because I really do think that the work I do is all about all of our futures. So, I don’t need to strike balance anymore in the same way that I needed to when I was younger. Now that said, one of the things that I have on my to-do list for looking forward is I, like many people, have become too connected all the time. So I’m looking for some ways to teach myself to disconnect a little more.

That’s probably the thing that I have on my personal adjustment list of things I want to focus on doing a little bit differently. And you know how hard it is, it really becomes a habit. We don’t realize because we’ve all sort of slowly worked ourselves into this habit, but now we have to undo this habit because it’s absolutely crazy that we’re all connected to our devices all the time and I’m very much guilty of that. I need to be more intentional about disengaging.

When you’re not working, what are your hobbies?

I do a lot of work in Baltimore, as I mentioned, I’m on a bunch of boards, I’m hands-on involved with a number of really interesting innovators and community leaders and activists. I play sports, I play tennis, I’m still very active. I work out a reasonable amount. I spend a lot of time with my family and I’m a passionate cook, so I cook all the time.

What’s your favorite meal to make?

I really don’t necessarily have a favorite meal. What I do have is this constant push for better. So, I’ll give you an example, something simple like roasting a chicken; anybody can throw a chicken in the oven and roast it, but there’s an incredible difference between a great roasted chicken and a not-so-great roasted chicken. For me, it’s not like there’s one thing I love to make the most, it’s more like I’m constantly tweaking, improving.

So, what’s next for you and for Generosity Inc.?

You know, I think for right now more of the same. I’ve been doing a bit more work advising for CEOs who want to incorporate mission into their enterprises, even if they don’t have a social purpose for their business itself but who view their life and their work as being very integrated. So, it’s been fun to work with some of those executives in addition to the work I do in some of the general movement building stuff.

That’s kind of a fun next step, but I’m very open to where all of this leads me—and as I said, part of that question you asked about success, for me, it’s very much about who I’m working with and what I’m working on.

Last modified on October 28th, 2016

Show Comments +